The fabric of Japan’s corporate sector has long been interwoven with the practice of corporate cross-shareholding, wherein two publicly listed entities reciprocally own shares. Historically, this practice, deeply entrenched in the business culture, has been a testament to the value placed on long-standing corporate allegiances, mutual trust, and a buffer against market turbulence. This tradition found its stronghold in the post-World War II era with the rise of Keiretsu conglomerates. These entities, bound by cross-shareholding ties, became instrumental in Japan’s rapid post-war industrial expansion and economic recovery, underpinning what would become the second-largest economy for decades.

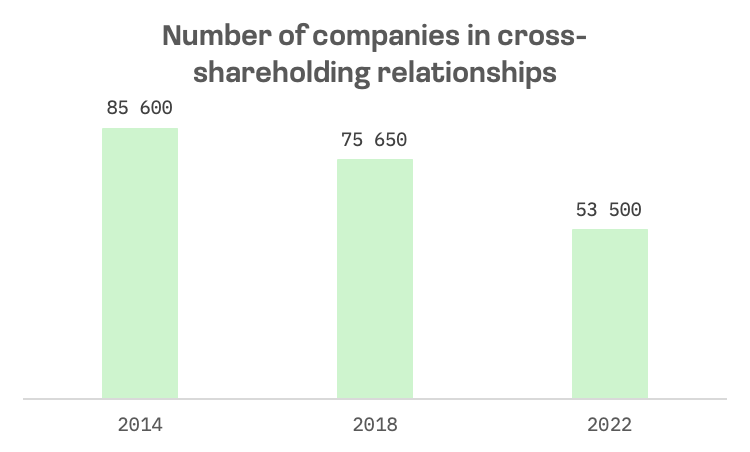

Nevertheless, the modern narrative of cross-shareholdings has evolved in response to the pressures of global markets and the need for more dynamic corporate strategies. A stark decline in this practice is observed, with the share of cross-held stocks amongst listed Japanese companies plummeting from about 70% of Tokyo Stock Exchange’s total market capitalization in 1990 to just over 30% as of fiscal year-end 2022, as per the Nomura Institute of Capital Markets Research.

Source: Nikkei Asia.

The scrutiny on cross-shareholdings intensifies with the perspective of financial returns. The 1990s witnessed a discernible erosion in the benefits once afforded by these practices, with the onset of an economic downturn marking a significant number of these assets as non-performing for banks and corporations alike.

The traditional network of cross-shareholdings also ensured a certain managerial stability. Boards, predominantly with executive tenure, facilitated a more uniform decision-making process. However, this insularity is believed to have contributed to the comparative productivity and competitive shortfall observed in Japan’s service sectors vis-à-vis their global peers. It’s a concern mirrored in the numbers, as the Return on Equity for Japanese firms hovers around 8-9%, notably lower than the 15-20% average of Western corporations.

The implementation of Japan’s Corporate Governance Code in 2015 marked a pivotal shift. The mandate was clear: disclose the purposes and the cost-benefit analysis of cross-shareholdings. Further revisions in 2018 and beyond have continued to press companies for greater transparency and more judicious management of these holdings. The table below elucidates key corporate governance milestones impacting cross-shareholdings, highlighting major revisions and their implications for disclosure and policy assessment.

| Timing | Major trend (entity in charge) | Key points of the revision |

| 2010 | Revision of the Ordinance on Disclosure (FSA) | Requires companies to disclose “specified investment shares” (cross-shareholdings) by issue in the Securities Report (each issue with value exceeding 1% of capital, or top 30 issues) |

| 2015 | Establishment of CG Code (FSA/TSE) | Principle 1.4 requires companies to disclose their policies regarding cross-shareholdings, and boards to assess the economic rationale of the shareholdings and disclose the results |

| 2018 | Revision of CG Code (FSA/TSE) | Principle 1 .4 requires companies to disclose their policies regarding the reduction of cross-shareholdings, and to assess whether the purpose of the shareholdings is appropriate in light of the cost of capital, and disclose the results |

| 2019 | Revision of the Ordinance on Disclosure (FSA) | Requires enhanced disclosure on cross-shareholdings in the Securities Report: – Criteria/concept of distinguishing shareholdings for pure investment purpose and shareholdings for other purposes – Method for assessing the reporting company’s policy on cross-shareholdings and rationale for the shareholdings – Details of the board’ assessment on cross-shareholdings in terms of the appropriateness of holding each issue – Number of issues, for which the number of shares increased/decreased from the previous year, and reasons for the increase – Raised the maximum number of issues to be disclosed (max. top 30 issues —> max. top 60 issues) – Full disclosure of each issue (the reporting company’s management policy/strategy, etc., benefits from the shareholdings in light of its business overview and segmental information, reasons for increasing the number of shares, existence of mutual shareholdings) |

| 2021 | Policy on proxy advice (Glass Lewis) | Recommends voting against the director, who is the top management, when the size of cross-shareholdings exceeds 10% or more of the net assets (published in 2019) |

| 2022 | Policy on proxy advice (lSS) | Recommends voting against the director, who is the top management, when the size of cross-shareholdings exceeds 20% or more of the net assets (published in 2020) |

The Corporate Governance Code has catalyzed a divestment trend in cross-held shares among Japanese businesses. In fiscal 2022, leading this move were Nippon Steel and Hitachi, both part of the JAKOTA Blue Chip 150 Index, with significant share sell-offs.

Nippon Steel’s divestment from 11 entities, including a complete stake sale in Suzuki Motor (JAKOTA Blue Chip 150 Index), underscores a strategic refocus, potentially channeling proceeds into decarbonization efforts.

Similarly, Hitachi’s divestiture actions were pronounced, with the company reducing its stakes in nine firms. The list of divestments includes notable companies such as Shin-Etsu Chemical (JAKOTA Blue Chip 150 Index) and materials manufacturer Resonac Holdings. This move was a result of a meticulous portfolio review that Hitachi conducted to evaluate the contribution of each holding towards the company’s capital efficiency, exemplifying the evolving corporate mindset favoring strategic over obligatory shareholding.

Kyocera, another index heavyweight, stands out with strategic shares amounting to nearly half of its net assets, predominantly in telecommunications behemoth KDDI birthed from a merger involving a former Kyocera unit. Kyocera’s leadership has explicitly stated, “since we do not hold the shares of KDDI Corporation for the purpose of cross-holding, nor do we hold them for the purpose to increase business transactions with KDDI Corporation, we believe that what ISS refers to in its report as ‘CROSS-SHAREHOLDINGS’ is clearly not applicable.” This statement underlines a distinct investment strategy that does not align with the typical practice of cross-shareholding.

As Japanese companies recalibrate their portfolios in response to governance codes and market pressures, the transformation in the landscape of cross-shareholdings is unmistakable. The journey ahead for these enterprises involves balancing traditional business harmony with the imperatives of a globalized economy, highlighting a period of strategic transition in Japan’s corporate governance realm.